Europe’s inflation problem has looked, at least on the surface, like yesterday’s drama. After the 2022 energy shock and a bruising burst of headline inflation, the subsequent disinflation felt reassuring — almost scripted. The European Central Bank (ECB)’s own staff macroeconomic projections from September 2025 point to inflation gradually converging back toward target and growth stabilizing.

But this apparent calm risks masking a more uncomfortable reality. The euro zone is drifting back toward a deflationary equilibrium through institutional stagnation, structural slack and weak core demand. The disinflation process may not end neatly at target. It may overshoot and become difficult to reverse.

The deeper problem is not primarily about the ECB’s competence, but about Europe’s political economy. Since the sovereign-debt crisis of 2011–2012, the currency union has relied heavily on the central bank as a stabilizer while failing to build the fiscal institutions needed to respond quickly and forcefully to shocks. Monetary policy has become the system’s default shock absorber; fiscal policy, by contrast, remains constrained by high debt, fragmented politics and slow collective decision-making. That mix tends to produce policy responses that are late, contested and too small — a classic recipe for chronic underdemand and renewed disinflation.

Why the past still matters

The euro crisis a decade ago was not so much solved as deferred. The ECB’s interventions, beginning with the commitment to do “whatever it takes” and later reinforced by bond-purchase programs, bought time. But that time was not used to reduce debt overhangs in high-debt countries or to complete a fiscal architecture capable of stabilizing demand when national fiscal space is limited.

The result is a structural asymmetry that has haunted the euro zone ever since. When shocks arrive — an energy spike, a banking wobble, a pandemic, a geopolitical rupture — national budgets in high-debt states are constrained, while European Union-level action is negotiated slowly. Economists can sometimes agree to joint borrowing, but typically only after delay and dilution. In macroeconomic terms, this produces an equilibrium in which demand support is systematically undersupplied.

In other words, Europe’s fiscal-governance debate is not mere constitutional theater. It shapes the inflation process itself. A system that cannot mobilize timely stimulus tends to generate persistent slack, which is disinflationary. If it endures, it becomes self-reinforcing as wage growth cools and inflation expectations drift down.

Slack moves to the core

What makes today’s environment especially dangerous is where the slack is concentrated. After the sovereign-debt crisis, Germany — the euro zone’s anchor economy — was still growing solidly, acting as a demand engine for the rest of the bloc. Strength in the core partly buffered weakness in the periphery.

That dynamic has now reversed. Germany is struggling. According to the European Commission’s economic forecast for Germany in November 2025, following two consecutive years of contraction, the economy was expected to stagnate in 2025, with only a modest recovery projected for 2026–2027. That is a grim profile for the euro zone’s largest economy, and it matters because Germany’s weakness is not contained within its borders.

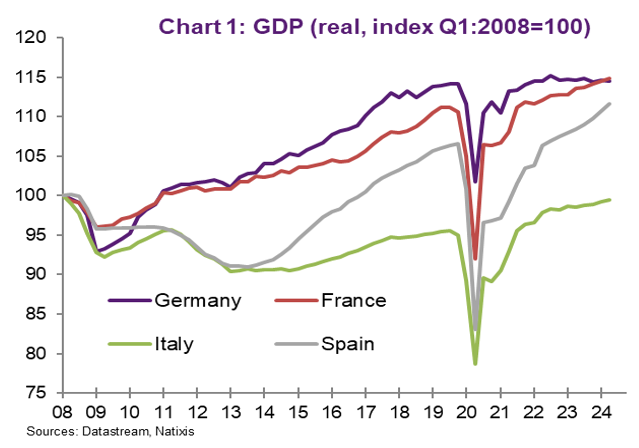

After a sharp rebound in activity during the second half of 2020 and 2021 following the initial Covid-19 shock, the German economy has entered a period of protracted stagnation. Real GDP in Germany is only marginally higher today than before the pandemic, in stark contrast to other large euro-area economies, where output has moved decisively above pre-pandemic levels (France: +3.8%; Italy: +4.7%; Spain: +4.7%). From a longer-run perspective, part of this divergence reflects catch-up elsewhere, as Germany had grown relatively strongly in the years preceding the pandemic.

Nevertheless, the chart below shows that this historical context does not explain away Germany’s current weakness: Even after accounting for earlier outperformance, Germany has failed to generate post-pandemic momentum while its peers have resumed sustained expansion. This points to a deeper and more persistent drag on euro-area demand emanating from the core.

It transmits through two channels: First, the real-economy channel. Germany sits at the center of Europe’s manufacturing and supply-chain network. When German firms cut investment and orders, the shock ripples through suppliers across Central Europe and beyond. Weak German demand becomes weak European demand.

Second, the institutional channel. Germany remains pivotal to euro-area fiscal politics. A weak Germany does not become a fiscal locomotive, but more likely a cautious one. Domestic political constraints, fiscal rules and coalition politics can all make ambitious demand support harder rather than easier — precisely when slack is spreading. Short-term data reinforce this picture. At the end of 2025, the euro zone’s manufacturing sector slipped deeper into contraction, with weak orders and continued price discounting, according to Reuters’ coverage of the Hamburg Commercial Bank Eurozone Manufacturing PMI. The survey singled out Germany as the weakest large economy covered. A separate Reuters report showed German manufacturing ending 2025 in a deepening downturn, driven in part by collapsing export orders.

If disinflation is returning to Europe, the geography matters. This time, it radiates from the core, not the periphery.

A note on measurement: output gaps are slippery

Any discussion of “slack” invites a methodological fight. Output gaps are commonly measured as the difference between actual GDP and “potential output,” but potential is unobservable. Many official estimates rely on time-series filters that track actual GDP too closely. In prolonged downturns, potential output is revised down alongside actual GDP, producing deceptively small gaps precisely when underperformance is persistent.

This is not a technical footnote. If slack is underestimated, stimulus will almost certainly be too timid.

Recent academic work has tried to address this problem. “Measuring the Euro Area Output Gap,” a 2025 study by researchers Matteo Barigozzi, Claudio Lissona and Matteo Luciani, uses a nonstationary dynamic-factor model on a broad dataset. It argues that since the sovereign-debt crisis, euro-area slack may have been mismeasured, with structural constraints playing a larger role than cyclical weakness alone.

The broader lesson is not that any single estimate is definitive, but that debates about slack quickly become debates about methodology. For policy analysis, transparency is preferable. Comparing actual GDP with a simple pre-COVID trend while acknowledging its limitations can be a more intuitive way to illustrate persistent demand shortfalls.

From low inflation to deflationary dynamics

Low inflation is not deflation. But the euro zone has lived through the process by which disinflation becomes entrenched. Persistent slack restrains wages, weakens firms’ pricing power and gradually pulls down inflation expectations. Once expectations drift, real interest rates rise even if nominal rates are cut, because inflation falls faster. Monetary policy becomes less potent precisely when it is most needed.

Late-2025 manufacturing data hint at this dynamic. Weak demand coincided with continued price cutting even as some input costs showed intermittent pressure, according to Reuters reporting. This combination of soft demand, cautious firms and discounting behavior is the kind of microeconomic texture that can pull inflation down over time, especially when growth is already weak.

Macro projections point the same direction. The ECB’s September 2025 outlook highlighted subdued foreign demand into 2026. The European Commission’s Autumn 2025 Economic Forecast likewise described modest growth and slowing potential output, with the euro area “broadly mirroring” a low-growth profile through 2027.

The risk, then, is not imminent collapse. It is a slow institutional drift into a world where weak demand becomes the default and inflation repeatedly undershoots.

Policy constraints in a weak global environment: what the ECB can’t do alone

The ECB still possesses powerful instruments. But recent experience has reinforced a hard constraint: monetary policy cannot reliably compensate for chronic fiscal shortfalls. Near the effective lower bound, easing works mainly through expectations, credit spreads and asset prices — channels that weaken when firms are pessimistic and governments are tightening rather than supporting demand. The ECB clearly reflects these limits in its own assessment of subdued demand and weakening inflation dynamics in its staff macroeconomic projections.

Fiscal policy, therefore, is the missing leg of stabilization. Yet across much of the euro zone, it remains constrained by high public debt and political resistance to deeper fiscal integration.

Even after the pandemic-era innovations, EU-level fiscal instruments remain too small, too conditional and too slow to counter large macroeconomic shocks.

This institutional bias toward insufficient stimulus gives the euro area its deflationary tilt: Demand support arrives late, at limited scale and often only after private-sector weakness has already become entrenched.

The global backdrop makes this constraint more binding. Europe’s drift toward low inflation is not occurring in isolation. Many major economies remain below their pre-pandemic growth trajectories. Persistent global demand weakness and slowing medium-term growth are documented in the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook, October 2024.

That removes an old escape valve. In earlier cycles, sluggish internal demand could be partially offset by strong foreign absorption. Today, with global slack widespread, domestic policy paralysis becomes harder to disguise — and its macroeconomic consequences harder to reverse.

What would prove this view wrong?

Europe is not facing a new crisis, but something more insidious: a gradual return to a low-inflation equilibrium driven by weak demand, fiscal inertia and a weakening core.

A deflation trap is not inevitable. This argument would be overturned by any of these three developments:

First, a genuine, scalable fiscal stabilization capacity at the euro-area level — one that can be deployed quickly, without prolonged wrangling, when shocks hit. This would require more than ad hoc crisis instruments. It would mean a standing fiscal mechanism with sufficient size, automaticity and political legitimacy to act counter-cyclically, especially in member states with limited national fiscal space.

Second, a sustained revival of German domestic demand, driven by investment and consumption rather than only temporary public-spending bursts. A potential caveat is Germany’s shift toward higher defense spending. In principle, rising military outlays could support domestic demand and soften disinflationary pressure in the euro-area core. In practice, defense spending translates into activity slowly: Procurement cycles are long, capacity constraints bind, and a meaningful share of spending leaks abroad via imports. Unless defense rearmament is paired with a broader, investment-led fiscal pivot — at scale and with speed — it is unlikely to offset structural slack.

Third, a durable rise in euro-area wage growth and inflation expectations under a genuinely symmetric policy regime — one in which undershooting the inflation target triggers as forceful a response as overshooting. Absent such symmetry, disinflation risks becoming self-reinforcing, pushing real interest rates higher and entrenching low-inflation dynamics.

Without these shifts, Europe’s institutional configuration is likely to keep producing the same macroeconomic outcome: chronic underperformance and a persistent pull toward low inflation.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

The post Europe’s Return to the Deflation Trap appeared first on Fair Observer.

from Fair Observer https://ift.tt/l0DI2Rb

0 Comments