A YouTube video dating from last January bears the title, “Will Trump’s billionaire brigade run America like a tech startup?” In it, Business Insider’s Media and Tech reporter Peter Kafka expresses his belief that “we are in a post conflict-of-interest world.” Commenting on the list of billionaires designated as members of Trump’s new administration, Politico’s tech specialist Derek Robertson agreed with Kafka. “We are beyond conflict-of-interest because these people are essentially setting policy for fields they stand to massively profit from.”

An article published this week by Business Insider informs us that there are now six members of an elite group of people whose personal fortunes are valued at more than $200 billion: Tesla CEO Elon Musk, Oracle cofounder Larry Ellison, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Meta cofounder Mark Zuckerberg, and Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. They are all American and they all appear to align with the political logic and ideology of US President Donald Trump. It is widely believed that they have all shared phone numbers with the president.

As Devil’s Advocate, I would hardly expect — now or in the future — to receive a request for the canonization of any of this crew. Most of them were present at Trump’s inauguration and all have demonstrated an “interest” in politics. The word “interest” has at least three meanings in this sentence. Curiosity and empathetic concern is one of those meanings, but certainly not the dominant one. “Intent to influence” is closer to the mark.

Most ordinary, rational people, typically engaged in making a living, would reason that if they were in possession of a measly one billion dollars — or even a few million — they would focus on the myriad ways available to them of enjoying their good fortune, rather than spending their precious time and vast resources seeking new opportunities to exercise their skills at managing conflicts of interest.

Was there really a pre-conflict of interest world?

Although it appears to some as a novel trend, this culture built around a post conflict of interest mentality didn’t wait for Trump to be elected to become either the defining trait of the US politico-economic system or its official ideology. Michael Douglas’s character Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film, Wall Street, famously intoned, “Greed is good.” Moving from New York’s Wall Street to Washington, DC’s Pennsylvania Avenue, the direct translation of Gekko’s wise words would be “conflict of interest is good.”

How does the current system work? And are Republicans the exclusive practitioners? In a recent article, political activist and writer Corbin Trent excoriated his fellow Democrats essentially for defending a supposed “moral order” that has long encouraged, to use his words, “selfish, narcissistic egoism” as the driving force of the economy. The difference is that what Democrats nourished passively and privately, Trump promotes brazenly and with his patented brio.

“Trump didn’t single-handedly infect our institutions. They were infected long ago. He’s just a selfish, narcissistic egotist who saw a weak government, weak institutions, a weak judiciary, and a weak opposition party, and took it over.

When Democrats focus all their energy on the exploiter rather than the rot that enabled him, they guarantee that nothing will change.”

So long as those who mastered DC decorum honored the prevailing system without advertising its flaws, they could count on the population’s resigned approval. The political custodians of the system, both Democrat and Republican, invested in defending it from criticism. Trent accuses the Democrats of identifying with an elite that wants to bring “us back to ‘normal,’” which he describes in the following terms: “Back to when people still struggled to afford the basics, when the USA was still a weakening nation, when all the broken and corrupted institutions that served their interests were humming along just fine. They just want to get rid of the madman who screwed up the good time they were having.” Trent even cites the deleterious role of “massive think tanks, policy shops, entire ecosystems dedicated to maintaining the status quo or getting us back to ‘normal.’”

In other words, any way you look — left (Democrat) or right (Republican) — candidates for sainthood among the political class will be few and far between. We are encouraged to think of think tanks as institutions that conduct high-powered research in the public interest. Many of them turn out to be exemplars of a special category: “conflict of intellectual interest.” Alas, the pattern even spills over into academia, which just as for the political class has its “revolving door.” Our intellectual establishment, private and public, finds itself at a far cry from the ideal expressed by English poet Geoffrey Chaucer seven centuries ago in the English of his time in his description of his “clerk of Oxenford” (Oxford cleric, a student and teacher):

Sownynge in moral vertu was his speche;

And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.

(Resounding with moral vertu was his speech;

And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.)

I’m not claiming that conflicts of interest didn’t exist in the 14th century, but intellectuals of the time could, according to the author of The Canterbury Tales, be content to simply study and teach.

The case of Bill Gates

How bad is it, really? Are there no cases of billionaires who put virtue above interest? On the contrary, we know about one: DFS Furniture cofounder Charles Feeney. He died two years ago, but not before giving his entire fortune away. He apparently had the same taste for personal austerity as Chaucer’s clerk.

But wasn’t there another one, much more a household name than Feeney? Who doesn’t remember the glorious image the founder of Microsoft managed to achieve, not so many years ago, as a paragon of public virtue? Some deemed him a veritable industrial saint. This achievement was particularly notable given that in the late 1990s most people perceived him as an unflinching, monopolistic corporate bully.

The wealthy have one distinct advantage over the rest of us: the capacity to hire people skilled in recrafting their image and spreading the new, improved version across the media. The basic requirement is to build the image around a noble cause. John D Rockefeller established the precedent after the Ludlow massacre in 1914, demonstrating that no-holds-barred capitalism could become sanctified through philanthropy. Rockefeller’s clever ploy, as he harnessed the talents of publicist Ivy Lee, effectively gave birth to the modern “science” of public relations. The rehabilitation narrative for the formerly reviled Gates had the added attraction of appearing as a classic tale of redemption.

How did Gates do it? He simply applied his business acumen to philanthropy, promoting a model that became labeled as “philanthrocapitalism.” He cleverly recruited the second-richest man in the world, Berkshire Hathaway Chair Warren Buffett, to accompany him and validate his claim. (The two often traded places as the uncontested world champion of wealth). This not only burnished Gates’s image, the media fawned over it for another self-interested reason: Gates’s conspicuous philanthropy appeared to justify predatory capitalism as an effective instrument of human welfare and collective prosperity.

Buffett was the perfect foil for Gates. Avoiding the spotlight, many saw him as a kind of innocent idiot savant who had mastered all the secrets of finance but, despite his visible wealth, maintained an austere, saintly lifestyle. This contrasted with Gates whose lifestyle was clearly flamboyant, despite the man’s singular lack of charisma. The media embraced the now thoroughly reformed “good billionaire,” who openly practiced enlightened self-governance alongside the genius investor from Omaha.

For several years, the public and the media perceived Gates as a problem-solving genius applying his purportedly exceptional intellect and efficiency-focused business models to the world’s most complex problems, including what is perhaps the most complex of them all: education. In that particular field, his formulas failed to work, but his wealth permitted him to persist.

Gradually Gates’s sanctified image began fading, at first imperceptibly, but it steadily eroded, notably when people discovered that the Gates Foundation — theoretically dedicated to noble causes such as health and education — was investing its wealth in companies known for gleaning profits from ignoble practices that compromised the health of both the planet and human society.

Bill’s candidacy for canonization finally imploded spectacularly when the media revealed his close relationship with human trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. That relationship was close enough in any case to incite Melinda, his wife and philanthropic alter ego, to sue for divorce.

During the Obama years in particular, Gates was one of the billionaires who more or less discreetly exercised disproportionate and unelected power over global policy. This became scandalously clear during the Covid-19 pandemic. His case suggests that great wealth may easily convert into an irresistible structural power that is at odds with democratic ideals, even when used for supposedly “good” ends.

The deeper roots of the post conflict of interest culture

The Trump administration has done nothing to disguise the omnipresence of conflict of interest within the political, financial and industrial world. But is it new, as Kafka and Robertson, cited above, suggest? Was it different in previous administrations? Six decades ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson had personal investment in both the defense industry and media and used his political clout to wage a disastrous war in Vietnam. He wasn’t being influenced by billionaires, but he was his own source of influence.

Without examining similar cases — and there are many — we should perhaps ask ourselves a more general question. We know that the US is a nation that maintains a quasi-religious belief in the idea of a natural affinity between democracy and capitalism. Hasn’t it now become obvious, in part thanks to Trump, that conflict of interest is a feature of the system rather than a vice to be avoided?

I discussed this very question with a colleague who made the following point. While conflicts of interest have always existed, the recent apparent disavowal of traditional ethical restraints and the unprecedented scope of private financial ties at the highest levels of government have led many to conclude that the system has transitioned from attempting to manage an undesirable vice to merely accepting and working within a de facto feature.

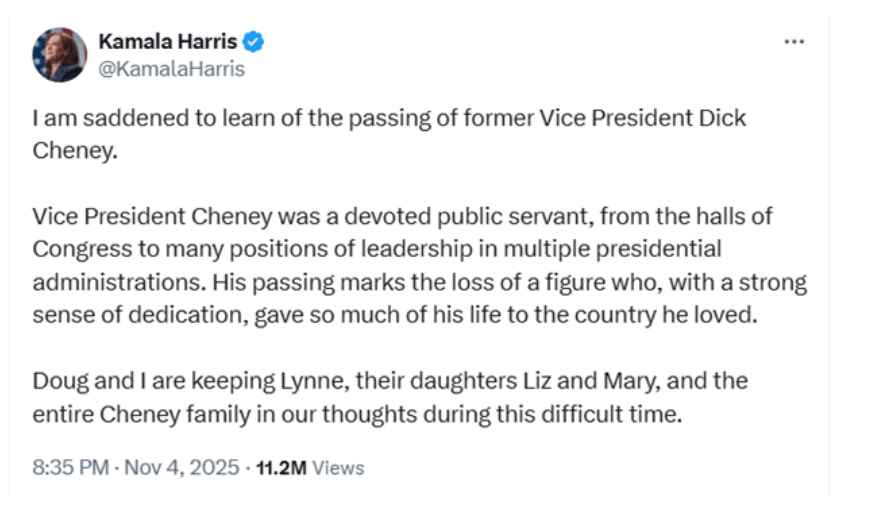

Looking for an illustration? Just this week, the most recent Democratic presidential candidate, Kamala Harris, upon learning of former Vice President Dick Cheney’s death, tweeted:

To what was Dick Cheney “devoted” as a “public servant” under President George W. Bush? One thing is uncontestable, he had no lack of devotion to the good fortune of the company he had previously managed as chief executive: Halliburton. Cheney continued to receive annual payments of deferred compensation from his former energy company throughout his time as vice president. He retained a large number of unexercised Halliburton stock options upon taking office. And of course, Halliburton’s good fortune mirrored — and contributed to — the ill fortune of millions of civilians in the Middle East.

And how did Halliburton do during his vice presidency? Halliburton’s subsidiary, Kellogg Brown & Root, received billions of dollars in no-bid or limited-competition government contracts for logistics and rebuilding work related to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Thankfully, no one has yet submitted a dossier of canonization for Mr. Cheney.

*[The Devil’s Advocate pursues the tradition Fair Observer began in 2017 with the launch of our “Devil’s Dictionary.” It does so with a slight change of focus, moving from language itself — political and journalistic rhetoric — to the substantial issues in the news. Read more of the Fair Observer Devil’s Dictionary. The news we consume deserves to be seen from an outsider’s point of view. And who could be more outside official discourse than Old Nick himself?]

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

The post Cheney, Trump and Billionaires Define Our Post-Ethics Era appeared first on Fair Observer.

from Fair Observer https://ift.tt/8PuWKRe

0 Comments